The INNOREDES Project has come to its end.

All the objectives were achieved and the results can be found in the INNOREDES Youtube Channel. You can Subscribe to our Channel here.

Also, we are glad to announce the launch of the second E-Newsletter.

The INNOREDES Project has come to its end.

All the objectives were achieved and the results can be found in the INNOREDES Youtube Channel. You can Subscribe to our Channel here.

Also, we are glad to announce the launch of the second E-Newsletter.

The INNOREDES Project is pleased to announce the Provisional Programme of the 2016 Barcelona Workshop on Regional and Urban Economics, to be held in Barcelona on October 27th-28th, 2016: [+]

The workshop will be focused on innovation and the spatial diffusion of knowledge with emphasis in collaboration networks. Its aim is to bring together researchers in urban and regional economics who are working in topics where the broad concept of the geography of innovation plays a fundamental role.

The keynotes speakers will be:

A round table will be held during the workshop with the participation of:

Participants will be required to register using the online form that is available at the workshop website until October 21st, 2016: [+]

For further information, please visit the workshop website www.ub.edu/aqr/workshop/2016 or contact to aqr_workshop@ub.edu.

Does innovation cause employment loses?

Using a panel of around 10.000 firms over the 2004-2013 period from the PITEC database, it is observed that employment is affected by the great recession experiencing a downturn. Concentrating on the dynamic behaviour of employment and if and how it reacts to innovation in firms, two alternative econometric estimations support the positive and significant impact of innovation on employment, both for product and process innovation. Employment in R&D follows a similar pattern, but, as expected, is much more sensible to the innovation variables. Our estimates also report that the growth of sales due to the introduction of new products is followed by an increase of net employment in firms. Contrary to the samples in other countries, we do not observe that the innovation process is causing employment loses.

Is this relationship different in the crisis?

Dividing our sample by subperiods, in order to investigate the impact of the Great Recession on this relationship, we conclude that firms that made process innovations created more (or less destroyed) jobs during the recession period. The policy implications of our findings confirm that innovation policies are not against employment creation. They should be persistent over time.

Firm heterogeneity is a crucial element for explaining export activity (Bernard et al., 2003). In particular, some empirical studies have compared the export performance of innovative and non-innovative firms, concluding in favour of a significant positive correlation between innovation and exports (e.g. Caldera, 2010; Becker and Egger, 2013). Building on this evidence, this paper shows that the effect of firm’s innovation on the propensity to export varies across regions. Using a representative sample of Spanish manufacturing firms, the effect of product and process innovation on the probability of exporting in each Spanish NUTS2 region is estimated. In a second stage, the estimated coefficients for each region are combined with the sample values of firm characteristics to compute counterfactual average propensities to export in each region, under a counterfactual scenario for the propensity to innovate in products and in processes. Comparison of actual and counterfactual regional export propensities allows a more intuitive assessment of the impact of regional differences in innovation on those observed in export performance.

Results in the paper show that innovative firms are more prone to export than otherwise similar non-innovative firms. For the entire of Spain, the probability of exporting for firms that declared to innovate in products was 35 percentage points (pp) higher than for similar firms that did not innovate. The size of the effect is similar for process innovation and for the measure that accounts for both types of innovations. Interestingly, results confirm substantial disparities across regions in the impact of innovation. The estimated increase in the probability of exporting associated to product innovation is above 40pp in Aragon and La Rioja, while on the opposite side, apart from the island regions, the lowest impact is shown by firms in Asturias and Catalonia. Regional disparities are also observed in the impact of process innovation, with the highest marginal effect in Murcia, Aragon, and Galicia, and the lowest in the two island regions, and in Asturias, and Andalusia. Overall, it can be concluded that the increase in the propensity of exporting due to innovation is larger in regions where the share of exporting firms is high; this result being robust to the alternative measures of innovation considered in the analysis.

The counterfactual exercise confirms that the increase in the share of exporting firms would be substantial in regions with an actual low extensive margin. Increasing the propensity to innovate in products leads to a rise of about 10pp or more in regions with a share of exporting firms far below the country average, such as Andalusia, Balearic Islands, Cantabria, Castile La Mancha, and Extremadura. In turn, the impact is much lower (3-4pp) in regions with a share above or about the country average (Valencia, Madrid, Navarra, and the Basque Country). A similar pattern is observed when using process innovation, though in this case the change in the above-mentioned share is less pronounced in all regions. The only region that clearly deviates from this pattern is the Canary Islands, as its extensive margin is the lowest in Spain while it is among the regions where the effect of increasing innovation is less intense. In fact, the correlation between the change in the extensive margin and its actual value in the set of Spanish regions excluding the Canary Islands is significantly negative (-0.70, -0.88, and -0.88 for product, process and both innovations respectively). This result leads us to conclude that, other things equal, increasing innovation propensity, particularly in products, would contribute to narrow the regional gap in the proportion of exporting firms.

An immediate implication of the evidence in this study is that policies aiming at stimulating innovation (for instance through technological cooperation), which are likely to be effective in promoting exports by increasing the number of exporting firms, will not exert the same effect on exports in all regions. Therefore, the a priori assessment of innovation policies should include the positive expected effect on export performance, but taking into account that geography and certain locational endowments are likely to affect the particular impact of these policies in each region. In addition, results on the effect of innovation on export status lead us to recommend focusing the effort of direct policies aiming at promoting exports just on the group of innovative firms in each region that are not exporting yet. They are the potential candidates to become exporters if locational disadvantages are compensated in some way by the effect of these policies.

Becker S. and Egger P. (2013) Endogenous product versus process innovation and a firm’s propensity to export, Empirical Economics 44, 329-354.

Bernard A., Eaton J., Jensen B. and Kortum S. (2003) Plants and productivity in International trade, American Economic Review 93, 1268-1290.

Caldera A. (2010) Innovation and exporting: evidence from Spanish manufacturing firms, Review of World Economics 146, 657-689.

Are there important differences in innovation and in R&D collaboration activities across Spanish regions?

It is observed that the share of innovative firms (in product and in process) varies substantially between regions, as it does the measures of firm’s absorptive capacity (performing continuous R&D activities, cooperate in innovation and employ high-skilled labour) and the external factors (GERD which is the share of the region’s gross expenditures in R&D on GDP, the percentage of population living in urban areas, the availability of highly educated workers, and the GDP per capita). Absorptive capacity, as measured by the three indicators, seems to be more abundant in regions in which the proportion of innovative firms is high, whereas it is scarce in those with low numbers of innovative firms. The share of firms performing R&D activities continuously is between one quarter and one third in Catalonia, the Basque Country, and Madrid, which is far beyond the numbers in low innovative regions (less and about 10 per cent). Similar disparities are observed as regard the proportion of firms that cooperate in innovation activities, whereas figures for the average share of highly skilled workers reveal that this type of labour is much more frequent in firms located in regions at the top of the innovation ranking; the opposite being also true. Overall, these figures suggest that regions differ sharply in the characteristics of their firms’ population, in particular with respect to those that determine the firm’s absorptive capacity. They also confirm, at the aggregate level, the positive relationship between absorptive capacity in general, and cooperation in particular, and innovation.

Do environmental factors related to innovation differ across regions?

We also confirm the existence of outstanding regional disparities in the environmental factors that have been told to affect firm’s innovation. Once again, R&D intensity is much higher in regions with a large share of innovative firms. Regions also differ as regard urban population and the endowment of human capital. However, the relationship with the share of innovative firms is not as clear for these magnitudes. For instance, the share of urban population in Catalonia, which is the region with the largest share of innovative firms, is below that in some regions with a much lower share of innovative firms (e.g. Asturias and Murcia). Similarly, the value of the measure of human capital in Catalonia is similar and even below that in less innovative regions (e.g. Aragon and Castile Leon). Finally, the per capita GDP figures reproduce the well-known regional disparities in productivity and income per capita in Spain. They are supposed to capture the effect of other external determinants of innovation that are not accounted for by the other three indicators.

Does the effect of cooperation activities vary across regions?

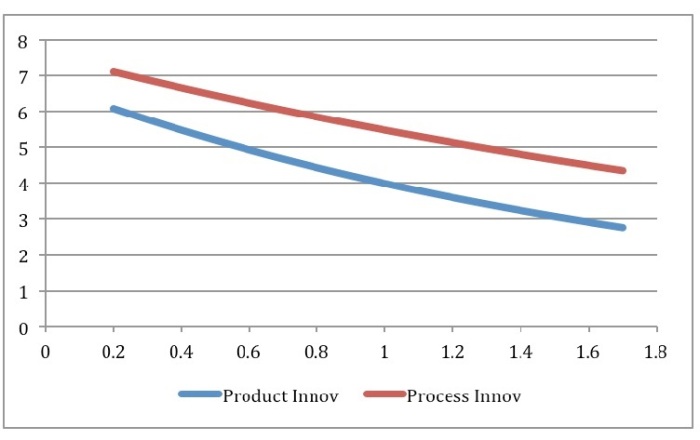

Estimates for the empirical model that accounts for the internal and external determinants of product innovation, including the interaction between the two, indicates that cooperation is a crucial element for the success of activities aiming at innovating in product in all firms. But it is more important for firms located in regions with a weak system of innovation than for those in regions characterised by a favourable R&D environment. As a matter of example, the probability of innovating in product is almost six times higher in the firms that cooperate and locate in the region with the lowest R&D effort (Balearic Isl.), while it is 2.75 times higher in the region with the highest (Madrid).

As for the results of process innovation, the gap in the probability to innovate in process between firms that cooperate and those that do not varies with the region’s R&D effort, being wider in regions in which the R&D environment is less favourable. This means that cooperating in technological activities is important when explaining innovation in process, but it seems to be crucial for firms located in regions in which the aggregate R&D effort is low.

The effect exerted by the level of R&D expenditures in the region on the impact of cooperation on product and process innovation is summarised by the figure below: stimulating technological cooperation could be an effective way of improving the innovation output in firms located in less favoured regions.

Effect of firm’s technological cooperation depending on the R&D effort of the region

Do Spanish firms collaborate in research activities with international partners?

Research alliances can be seen as a vehicle for voluntary knowledge exchanges. Descriptive statistics, based on our sample of Spanish firms from the PITEC, show that the proportion of international alliances with partners in more distant geographical areas (US, China, India and other countries), although lower in number if compared to research alliances with geographically closest partners, has increased over the period 2004-2011. This suggests that firms are expanding technological interaction with different and increasingly geographically dispersed actors.

Percentage of cooperative firms by type of alliance

| 2005 | 2007 | 2009 | 2011 | |

| % Cooperative firms over innovative firms | 0.358 | 0.339 | 0.353 | 0.378 |

| Geographical areas of alliances (% of each category over cooperative firms) | ||||

| National exclusively | 67.76 | 64.20 | 62.53 | 58.18 |

| International exclusively | 5.12 | 5.25 | 4.32 | 4.46 |

| National & International | 27.12 | 30.54 | 33.15 | 37.36 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| International alliances | ||||

| European exclusively | 79.86 | 71.09 | 75.49 | 69.57 |

| US exclusively | 3.60 | 7.03 | 6.86 | 6.52 |

| Asian/Others exclusively | 7.19 | 6.25 | 9.80 | 11.96 |

| Multiple foreign areas (at least two) | 9.35 | 15.63 | 7.84 | 11.96 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Are national and international collaboration agreements equally beneficial?

We find that the impact of extra-European cooperation on innovation performance is larger than that of national and European cooperation, indicating that firms tend to benefit more from interaction with international collaborators as a way to access new technologies or specialized and novel knowledge that they are unable to find locally. Our findings also show that extra-European alliances, especially with US partners, impact on innovation more importantly probably due to the fact that in some sectors, the US conducts research at the technological frontier. But also cooperation with other areas has a greater impact on innovative performance than national alliances.

Which is the role of absorptive capacity on the returns to collaboration agreements?

We find evidence of the positive role played by absorptive capacity, concluding that it implies a higher premium on the innovation returns to cooperation in the international case and mainly in the European one. Firms that have high absorptive capacity are more efficient at translating external knowledge from cooperative agreements into new, specific commercial applications. Further, this absorptive capacity seems especially efficient when the partner is international, probably due to the fact that such absorptive capacity gives the ability to better understand and assimilate the knowledge from a different national system of innovation. Interestingly enough, we obtain that although cooperating exclusively with European partners may imply benefits, they do not seem to surpass the costs of managing such international cooperation unless the firm combines it with a higher absorptive capacity to reduce the barriers posed by national differences.

AQR-IREA is pleased to announce the 2016 Barcelona Workshop on Regional and Urban Economics, to be held in Barcelona on October 27th-28th, 2016.

The workshop will be focused on innovation and the spatial diffusion of knowledge with emphasis in collaboration networks. Its aim is to bring together researchers in urban and regional economics who are working in topics where the broad concept of the geography of innovation plays a fundamental role. Particular attention will be paid to papers dealing with the mechanisms and actors of knowledge diffusion (knowledge spillovers, networks, technological collaboration, and knowledge relatedness). Although the Workshop will focus on empirical papers, theoretical studies are also welcome.

The keynotes speakers will be:

Audience: We will accommodate around 8-10 papers, to be presented in plenary sessions that will complement the keynote speakers’ presentation.

Important dates:

For further information, please visit the workshop website www.ub.edu/aqr/workshop/2016, or contact to aqr_workshop@ub.edu.

A relevant issue in the knowledge externalities literature is whether firms located in agglomerations mainly learn from other local firms in the same industry or from other local firms in a range of other industries (Glaeser et al, 1992). A second form of externalities relates to Jane Jacobs’ contributions on cities, externalities and innovation (Jacobs 1969). From her work we learn that a diversified economy would bring benefits to local firms because it would generate new ideas steaming from the cross-fertilization of ideas across different industries. In a regional context, this would be in line with the idea that regions with a more diverse stock of knowledge would have a greater potential for innovation and growth. However, since the paper by Frenken et al (2007), several authors have argued that the concept of diversification claimed by Jacobs need to be more deeply specified, by separating between diversification of related industries and diversification of unrelated industries – or, using the correct jargon, related versus unrelated variety. Regions hosting related industries, with different but connected knowledge bases, can more easily engage in recombinant innovation. On the contrary, the combination of previously unrelated industries or technologies is more difficult to succeed.

We study in depth the relationships between the local knowledge economy and the knowledge that flows from other regions in generating new knowledge. In particular, we assess whether the more similar the internal and external knowledge sectors, the larger the innovation outputs, or else, different but related internal and external sectors are more prone to innovation creation. We use a sample of 274 NUTS2 European regions of 27 countries from 1999 to 2007.

We obtain that similarity between the technological composition of the knowledge of the within-the-region patents and that of the cross-regional co-patents has a highly significant impact on the regions’ innovative output. In other words, if the knowledge that enters a region thanks to collaboration agreements with inventors in other regions is from sectors in which it already patents, there is plenty of room for absorbing new knowledge, with the subsequent significant impact on innovation output.

On the contrary, if only a certain degree of relatedness between the technological sectors of the patents in the region and the technological sectors of the knowledge flows that come from co-patenting with inventors in other regions exists, the interconnection does not seem to produce any significant innovation outcome but a higher similarity is needed. However, when the patents are weighted by their quality, the positive and significant parameter of the relatedness index suggests that the connections made with inventors outside the region have a relevant impact on its innovation output as far as the co-patenting profile (the knowledge that enters the region from the external world) and the knowledge stock of the region are related to a certain extent, but are not very similar. This is probably the case because the possibilities to learn different competences are wider in such a case and seem to be needed to generate more radical innovations. We can conclude, therefore, that in order to develop the exchange between inventors belonging to different technological sectors, it is necessary to have a certain level of similarity so as to have the opportunity to learn from each other, but this is not so much the case for breakthrough innovations, where just some relatedness between the knowledge inside and outside is necessary.

Glaeser, E.L., Kallal, H.D., Scheinkman, J.A. and Shleifer, A. (1992) Growth in Cities, Journal of Political Economy 100(6): 1126-1152.

Frenken, K., F. van Oort and T. Verburg (2007) Related Variety, Unrelated Variety and Regional Economic Growth, Regional Studies, 41(5), 685–697.

Jacobs J (1969) The economy of cities. Random House, NewYork.

Using information from the Technological Innovation Panel (PITEC) for Spanish firms we observe that Spanish firms tended to choose simultaneously several types of partners to carry out their innovation activities: customers and suppliers (vertical cooperation), competitors (horizontal competition) and institutions and research centres. Around 48% of the enterprises that decided to cooperate did so with at least two types of partners, and almost 14% cooperated with the three types of partners at a time.

| R&D cooperation strategies among Spanish innovative firms | ||||||

| I | V | H | Strategies | Firms | % | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | Non-cooperation | 4842 | 65.8 | |

| 1 | Only Horizontal | 80 | 3.2 | |||

| 1 | 0 | Only Vertical | 436 | 17.3 | ||

| 1 | Vertical + Horizontal | 50 | 2.0 | |||

| 1 | 0 | 0 | Only Institutional | 788 | 31.3 | |

| 1 | Institutional + Horizontal | 132 | 5.2 | |||

| 1 | 0 | Institutional + Vertical | 683 | 27.1 | ||

| 1 | All strategies | 351 | 13.9 | |||

| Total innovative firms with at least a cooperative agreement | 2520 | 34.2 | ||||

| Horizontal R&D cooperation (H)* | 613 | 24.3 | ||||

| Vertical R&D cooperation (V)* | 1520 | 60.3 | ||||

| Institutional R&D cooperation (I)* | 1954 | 77.5 | ||||

| * H: Competitors; V: Suppliers and/or Customers; I: Consultants, commercial labs or private R&D institutes; universities; government or public research institutes; technological centres. 0 indicates NO and 1 indicates YES.

Note: Except for the 2 values in bold, the rest of % are computed over the total number of firms cooperating. |

||||||

Related to the drives of R&D cooperation we confirmed that, in the case of Spanish firms, incoming spillovers were an important determinant of the choice of cooperating with any type of partner, regardless of the sector, but this impact was significantly higher in the case of partnerships with research institutions and universities. This result is consistent with the notion that firms which are able to get more benefits from external knowledge might be more likely to engage in cooperation agreements with the research base or, at least, with firms outside their own industry. Similarly, public funding also played a key role in the firms’ decisions to cooperate, especially when the partners are research institutions. This may be related to the fact that much of the public funding for innovation aims to encourage and promote knowledge transfer from research institutions to companies. Results also show that large firms are more likely to cooperate with all types of partner than small firms, highlighting the fact that large firms are more likely to face the commitment required in partnerships and better reap the returns of cooperation agreements.

The differences found among the main determinants of R&D cooperation across sectors are also of great interest. In the case of Spanish firms, there was a greater propensity to cooperate in the service sector (40%) than in manufactures (31%). Additionally, this lower probability of R&D cooperation for manufactures was more pronounced in the case of horizontal cooperation (with competitors). This can be related with previous findings suggesting that in the manufacturing sector, for which legal protection methods are in general more important than for the service sector, cooperation may act as a substitute to legal protection through patenting. Also, the results point to the fact that firms in the service sector see cooperation agreements as an effective way to enhance and complement their human resources for carrying out R&D activities. These differences are presumably due to sectoral differences in the orientation of innovations in industrial and services firms, since, for instance, innovation is more closely involved with worker skills in the services sector than in manufactures, where machine and equipment play a more important role in the innovation process.

The Community Innovation Survey allows to compare innovation and competiveness of firms, industries, and countries across Europe. It includes EU member states and Iceland, Norway, Croatia, Serbia and Turkey (with some exceptions across the seven waves). In here, we consider the last five waves (i.e. 2004-2012) for a most comprehensive picture, since in 2004 new member states were included in the survey.[1]

In the period considered, more than 700,000 companies participated in the survey each year; of these, about one-third declared to have undertook innovation activities[2]. Countries differ significantly in terms of the innovation behaviour of their firms. Fig. 1 shows the share of innovative enterprises on total enterprises by country and wave, ordered by the average shares over the four waves. The average share of innovative firms ranges from the highest one of Germany (64%) to the lowest one of Romania (16%). Spain occupies the second half of the ranking, with an average share of innovative firms of 30%. Such variety is pervasive also in terms of the trend across the years. In particular, Spain shows a decreasing pattern; in 2004, the share of innovative firms is 35%, while in the last wave drops to 23%. Similar declining trends are shown by Poland and Estonia, while Malta is the only country with increasing shares; the remaining countries exhibit more fluctuating trends over the years.

Fig. 1 – Share of innovative firms on total firms

Source: EUROSTAT, Community Innovation Survey

R&D cooperation among EU countries concerns about one-quarter of innovative firms (average on the four waves). Fig. 2 shows the shares of cooperative innovative firms by country and wave. The country ranking lowest is Italy (13%), while Cyprus is the country with the highest share (54%). In the last two waves, the percentage of cooperative innovative firms of EU members increase from 25% in 2010 to 31% in 2012. Spain collocates among the bottom rows with an average share of 21%. Spain is among the countries which significantly increase the share of cooperative innovative firms in the latest years, from 22% in 2010 to 29% in 2012; similarly, Belgium increases its share from 42% in 2010 to 52% in 2012, while other countries experience a decline instead, such as for example Luxembourg (from 32% in 2010 to 20% in 2012). However, likewise the statistics on the share of innovative firms discussed above, the shares of cooperative innovative firms for each country tend to fluctuate over time. In the case of Spain, the combination of a decrease in the share of innovative firms as discussed above and an increase of the share of cooperative innovative firms signal a possible reinforcement of the links between technological cooperation and innovativeness, meaning that the firms which manage to be innovative are also cooperating to a significant extent.

Fig. 2 – Share of innovative firms with any type of cooperation

Source: EUROSTAT, Community Innovation Survey

Firms rely on both internal and external sources of knowledge to sustain their competitive advantage. With respect to R&D expenditures, the Community Innovation Survey provides data for in-house R&D and external R&D (i.e. R&D contracted out to other enterprises or research organisations). Fig. 3 shows the shares of innovative firms with internal and external R&D by country, averaged on the period 2004-2012. Firms from EU-28 countries which are engaged in internal R&D constitute 39% of innovative firms, while only 18% of innovative firms carry out external R&D. For internal R&D, Bulgaria has the lowest share (11%), while Finland ranks at the top (77%). In terms of external R&D, the lowest share belongs to Malta (6%), while Finland has the highest one (32%). Spain stays in the bottom-half of the ranking, both in terms of internal R&D (35%) and external R&D (19%), although the latter is slightly higher than EU-28 average.

Fig. 3 – Average shares of innovative firms with internal and external R&D, 2004-2012

Source: EUROSTAT, Community Innovation Survey

By looking at the trends over the period 2004-2012, the shares of innovative firms with internal R&D in Spain vary across time as shown in Fig. 4, with the highest figure registered in 2012 (41%), about two percentage-points above EU-28 countries in the same year. About the trends of external R&D showed in Fig. 5, Spain experiences a lower point in 2004, and then a steady increase until 2012, where the percentage of innovative firms with external R&D reaches the same level as in 2004. The increase of both internal and external R&D in the latest years suggests an intensification of the linkage between R&D expenditures and innovation for Spanish firms; if we consider the decreasing trend of the share of innovative firms in the period considered, this suggests that for the firms which manage to stay (or start to be) innovative, R&D remains an important source of knowledge.

Fig. 4 – Share of innovative firms with internal R&D, 2004-2012

Source: EUROSTAT, Community Innovation Survey

Fig. 5 – Share of innovative firms with external R&D, 2004-2012

Source: EUROSTAT, Community Innovation Survey

[1] We consider the following core innovative sectors for 2004-2006: Mining and Quarrying; Manufacturing; Electricity, gas, water supply; Transport, storage and communication; Financial Intermediation; Wholesale trade and commission trade, except of motor vehicles and motorcycles; Computer and related activities; Architectural and engineering activities and related technical consultancy; Technical testing and analysis. For 2008-2012: Mining and Quarrying; Manufacturing; Electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning supply; Water supply, sewerage, waste management and remediation activities; Wholesale trade, except of motor vehicles and motorcycles; Transportation and storage; Publishing activities, Telecommunications, Computer programming, consultancy and related activities, Information service activities; Financial and insurance activities; Architectural and engineering activities; technical testing and analysis.

[2] Innovative firms are those which have product or/and process innovation, regardless of organisational or marketing innovation, including enterprises with abandoned/suspended or on-going innovation activities.